Religion on the Reservation

Religious Beliefs of the Kiowa (Pre-Removal)

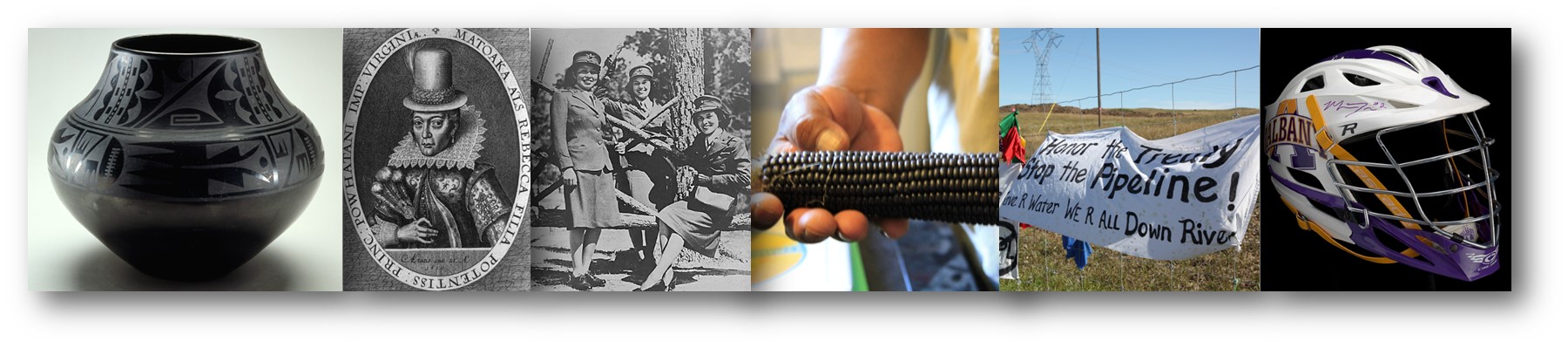

Like many nations, the Kiowa believed in a world of spirits which could take the form of animals, natural phenomena like whirlwinds and thunder, and even celestial bodies such as the Sun, Moon, and stars. These spirits all possessed varying levels of a universal power called dwdw. Spirits believed to have the greatest dwdw earned a special place of reverence. Kiowa religious practices were closely entwined with secular society and the two were often indistinguishable. Religion was not seen as a fixed institution, but rather as a means by which higher powers could be harnessed for the good of society. The pursuit of this power was often encouraged even if it meant incorporating new rituals and beliefs into the existing system. For the Kiowa, an individual wishing to gain dwdw for themselves had to undergo a vision quest, which entailed four days of praying, smoking, and fasting. If one was lucky enough to receive a vision they would acquire war or healing powers, but never both. Referred to as medicine, war medicine granted enhanced protection and healing medicine greater curative abilities. Dwdw secured one’s place among the elite and individuals with these powers carried immense influence in society. Traditional beliefs faded from practice as the items needed to conduct certain ceremonies became increasingly difficult to acquire in the face of buffalo extinction, forced removal, and restrictions on hunting.

Religion on the Reservation

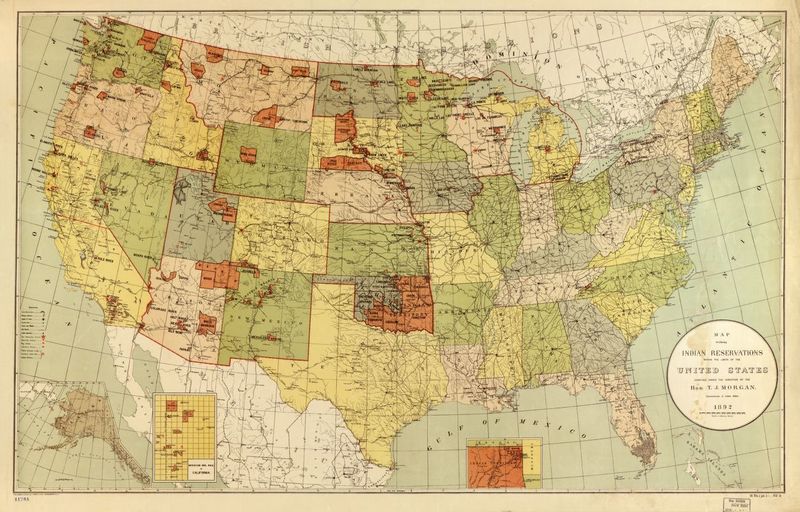

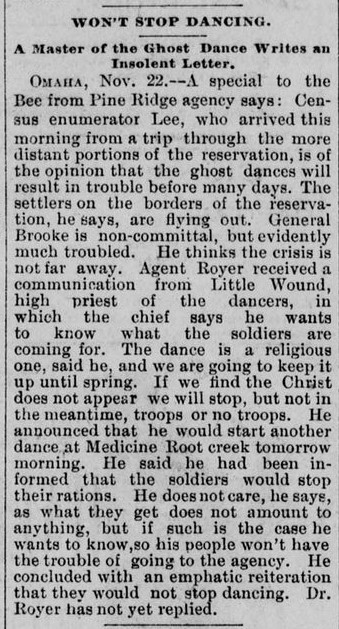

By 1875, the Kiowa and several other nations such as the Comanche, Arapaho, and Cheyenne were largely confined to a reservation in the Indian Territory, today called Oklahoma. There, under the watchful eye of a military garrison at Fort Sill, the federal government began their focus to “civilize” the Natives by introducing them to western concepts while simultaneously outlawing traditional Indigenous practices. Christian proselytizers constructed missions on the reservation and won small numbers of converts, who were impressed by the missionaries’ aid in the process of “Americanization.” Indigenous beliefs began to reflect the presence of these missionaries as new religious movements with Christian syncretism gained popularity. The Ghost Dance first came to the Kiowa in 1890, who highlighted its similarities with Christianity to try and prevent government agents from preventing the dances. Some practitioners even claimed the dance was a nativized version of Christianity and prophesized the return of Jesus Christ. In either case, the Ghost Dance was a lament for what was lost. Ritual leaders claimed the ceremony allowed communication with the dead, and that it would bring about the return of the buffalo, which had recently been hunted into extinction. Native leaders argued with government authorities that the Ghost Dance and other religious movements were constitutionally protected, but those in charge of Indian policy did not view Indigenous people as developed enough to take advantage of the rights given to other citizens. Those who participated in the Ghost Dance were threatened with forced labor, imprisonment, fines, and more.

Native American Religion Today

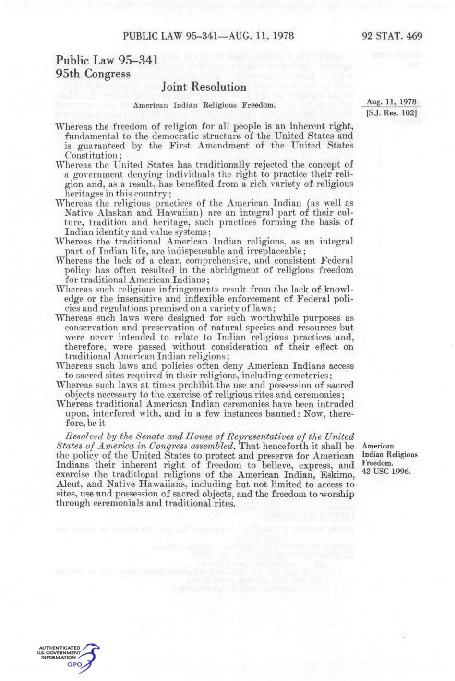

From the early days of reservations until very recently, Native American beliefs have not benefitted from equal protection and the right of religious freedom. Early religious persecution was based on assimilation into Anglo-American culture. In the early twentieth century, the idea of “Americanization” was abandoned by most policy makers as racial identity began to define most interactions between the government and the Indigenous population. Agents of the Bureau of Indian Affairs stopped focusing on “civilizing” the Natives and more on open suppression. The Native American Church, founded in 1918, had many of its ceremonies outlawed because of the use of peyote, a hallucinogenic cactus. These constitutional violations remained in effect until the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978. It was then, in clear terms, that the federal government acknowledged that Indigenous nations had been unable to practice their beliefs and their religious rights had been violated. In an amendment to the act, the ritualistic use of peyote was legalized, thus formally protecting certain ceremonies of the Native American Church. According to anthropologist Benjamin Kracht, the modern Kiowa religious landscape is a blend of Christian, peyote, and traditional beliefs. The majority of members identify as Christian, although only seventeen percent of church members attend regular service. The Native American Church suffers a similar problem with decreasing participation as a younger Kiowa generation moves away or seeks alternative beliefs. The elders remain respectful of all religions and push the importance and power of prayer on their community.